Thoughts from Inside a Heat Dome

Certainty, searching and ceremonies

Trying to engineer certainty in an apocalypse

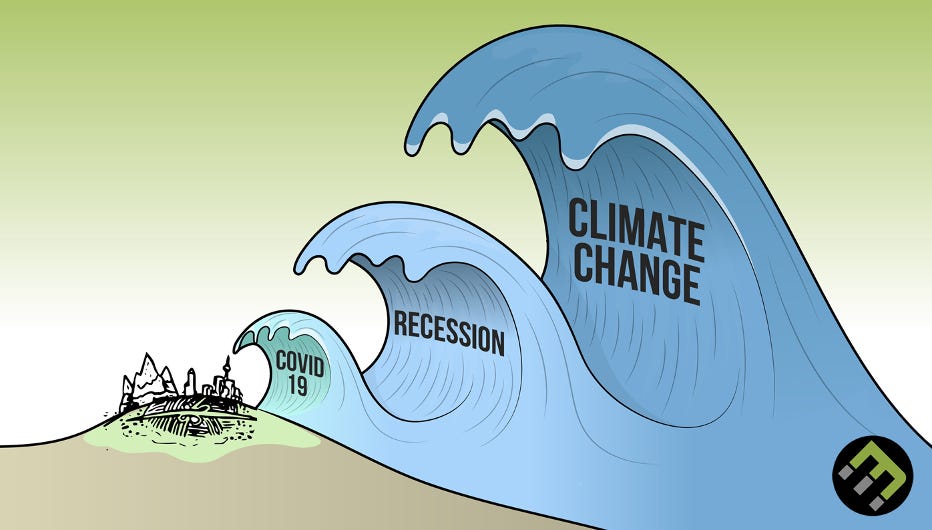

I recently heard anxiety described as “a disturbed relationship with certainty.” In a way, I moved to France in 2022 in pursuit of certainty…

The pandemic had kept me from seeing my family for two years. I knew it was time to reduce the distance between us. Having witnessed the vapour trails disappear from the blue skies over South Africa’s Western Province, it seemed plausible that, one day, air travel might not be something I could take for granted.

“Besides,” I thought, “maybe it’s a good thing to get out of Cape Town. After all, it was nearly the first city to have its taps run dry from climate change and the wildfires are getting out of control. Maybe we’ll be better off in Europe.”

I’ve written about the fantasy that drew me to France before, but I didn’t mention the deep climate anxiety that gave it wings.

Yes, I wanted “small-town-living with clean air, quiet streets, recognisable faces, a patch of land to grow some food on, and my family nearby…” But part of why I wanted those things was because I was terrified of particulate matter. I was terrified of the run on supermarkets in Cape Town for bottled water when the taps threatened to dry up and for yeast when lockdown happened. I was terrified of the idea that in an emergency, I don’t even know who my neighbours are.

“I text a friend, “I can’t find bread flour.” She lives in Iowa. “I can see the wheat,” she says, “growing in the field from outside my window.” I watch a video on how to harvest wheat. I can’t believe I have no machete. I can’t believe I spent so many hours begging universities to hire me, I forgot to learn how to separate the chaff from the wheat and gently grind.” - Sabrina Orah Mark, “Fuck the Bread. The Bread Is Over.”

To cope with the fear, the tendrils of my mind set about orchestrating certainty. If I could just find a cheap piece of land — outside of a flood zone, mind you — where I could build an eco-house engineered to withstand extreme weather and where I could learn how to grow food then maybe, just maybe it would be alright. And with my family just down the road, surely we’d all survive together.

Perfectly formed and dead

In 2022, the year Deb and I moved to France, the country was hit by three summer heatwaves. Temperatures regularly reached 40˚C. There was a record rainfall deficit. The way I remember it, we didn’t see rain for three months. The land was put under such incredible strain that the leafy forests that cover much of the Lot turned brown — their leaves falling off from drought stress.

When finally, some time in late August or September, a thunderstorm finally formed over the dead earth, I stood out in the hot downpour in exhausted relief. I had suffered deeply all summer from behind the shutters. My distress was profound. Part of it was simple, natural grief. But part of it was because the certainty I’d hoped to find in France was clearly misguided. It was clear — no one and nowhere would be spared.

I write this now in 2025 from the heart of the second heat dome to settle over France this summer. The fan is cranked up to 12. The dogs drift in and out of a dull torpor. And I reach over to the spray bottle on my desk regularly to mist my face.

I’m on anti-anxiety medication now. The summer of 2022 is what finally broke me. I swallowed my first tablet one unusually hot Sunday morning in October of that year and I recorded this audio diary…

I stand by my decision. Debilitating anxiety is no way to live out whatever is left. I want to live out my days in connection. But now I can watch the leaves of my beloved oak tree in the backyard die and fall without the very ground I stand on spiralling away from me, and I wonder if I was more connected then or now…

“In a mad world, only the mad are sane.”

―Akira Kurosawa

In the evenings, when the mercury drops to 30 — the same temperature as inside the house — we open the doors and windows for fresh air. If we’re lucky, by 11pm it’s in the mid 20s and I can lie on top of the bed to read my book in the relative cool.

I’m reading Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko. The book follows the story of Tayo, a half-Pueblo, half-white man, after his return from World War II, and the spiritual journey he goes on to get some relief from his psychological pain. His pain is both from the trauma and loss he experienced during the war, but also from the deep gash in his soul inflicted by “the destroyers” — the white colonisers and their now offspring.

Their highest ambition is to gut human beings while they are still breathing, to hold the heart still beating so the victim will never feel anything again. When they finish, you watch yourself from a distance and you can’t even cry — not even for yourself. - Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

Reading about a wisdom tradition has made me acutely aware that I come from a dead culture. The very marrow of our globalised Western society is rotten.

“The destroyers had tricked the white people as completely as they had fooled the Indians, and now only a few people understood how the filthy deception worked […] The effects were hidden, evident only in the sterility of their art, which continued to feed off the vitality of other cultures, and in the dissolution of their consciousness into dead objects: the plastic and neon, the concrete and steel. Hollow and lifeless as a witchery clay figure. And what little still remained to white people was shrivelled like a seed hoarded too long, shrunken past its time, and split open now, to expose a fragile, pale leaf stem, perfectly formed and dead.” - Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

Reality is interconnection

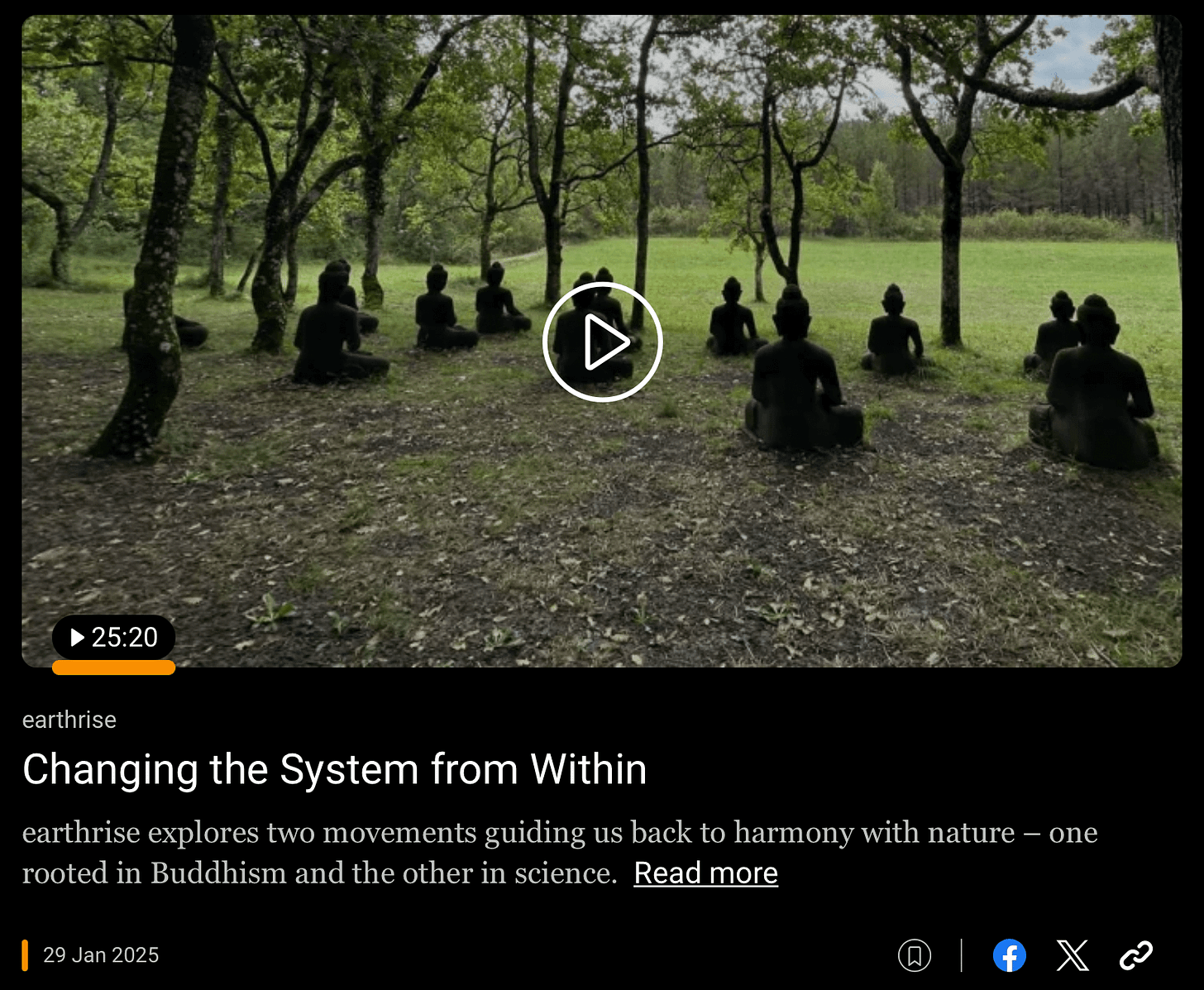

One particularly soporific afternoon I close my work tabs and click on one I’ve kept open for six months. It’s time to finally watch the episode of Earthrise that my mum shared with me in February. It features Plum Village, the largest Buddhist monastery in Europe. I took a road trip there with a friend not too long ago.

If you have spent any time on my Substack, you’ll know that I’m casting around, searching for an answer to the question that journalist Dahr Jamail asks in this series of articles for Truthout: “How then shall we live?”

And yes, given my hollowness, I have turned to “the vitality of other cultures” for answers — to Buddhist philosophy and yoga…

So I sit back in my chair and press play. My ears sweat from the headphones and my heart aches from the message…

It’s the words of Erik Fernholm that stay with me:

“Reality is interconnection, but our narrative is separation. Us acting out the narrative of separation is what’s causing unsustainability. […]The way we are solving problems is the problem. And that means we need to change [internally] if we want to see a better future.”

New ceremonies

I have found my strongest guidance from wisdom cultures that are not my own. But I have also tried to see what might be salvaged from the shrivelled seed of my ancestry. “Just as I stand on the edge of Indian culture looking in, I stand on the edge of Gaelic/ Celtic/Pagan culture looking in, and I find myself wondering, ‘Can I really feel at home in it?’”

I can’t say I’ve found my way, but I do keep coming back to herbalism and dreams, symbols and stories. Things I shyly classify under a kind of “witchcraft”. But one that I stumble through — hesitant and abashed.

From #WitchTok to books online, I find myself baulking at the New Age, neoliberal commodification of it all and I’m made uneasy by the thought that, because our culture died, we’re all just making it up as we go along.

But there’s a line in Ceremony from an old medicine man that gave me pause:

“Long ago, when the people were given these ceremonies, the changing began, if only in the ageing of the yellow gourd rattle or the shrinking of the skin around the eagle’s claw, if only in the different voices from generation to generation singing the chants.[…] After the white people came, elements in this world began to shift; and it became necessary to create new ceremonies. […] Things which don’t grow are dead things.” - Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

Perhaps in order to be “more aligned with reality,” as Erik Fernholm puts it, “the reality of interconnection, the reality that you are nature,” we need to give ourselves the grace to find these new ceremonies. To revive ourselves from the dead, even if it means making it up as we go along. Because to make it up, we first have to listen to what is being called for.

And perhaps that listening can be as simple as a moment like this:

"Up ahead, a snake stopped and raised its head alertly; the tongue slid in and out and then stopped when it located [Tayo]. It was a light yellow snake, covered with bright copper spots, like the wild flowers pulled loose and traveling. It crossed the wash and wound its way up the slope, disappearing into the grass. He knelt over the arching tracks the snake left in the sand and filled the delicate imprints with yellow pollen.”